Inhale on 1, on 2 on 3. Exhale on 1, on 2 on 3. Leg raises can seem a little boring and I sometimes feel a pang coming to that point in the class. I try to encourage students not to throw them away by inviting them to count the breath, close the eyes and lift as far as there is a straight leg. But this warm up is not just about lengthening the hamstrings for greater flexibility.

Inhale on 1, on 2 on 3. Exhale on 1, on 2 on 3. Leg raises can seem a little boring and I sometimes feel a pang coming to that point in the class. I try to encourage students not to throw them away by inviting them to count the breath, close the eyes and lift as far as there is a straight leg. But this warm up is not just about lengthening the hamstrings for greater flexibility.

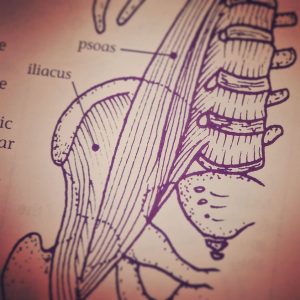

There’s a muscle hidden deep in body that snakes from each side of the bottom ribs to the top of the thigh. 40 cm long or so, it goes close to the inside of the spine, scoops under the abdominal organs, passes either side through the pelvis and attaches about 10cm down the inside of the femur (thigh bone). It’s skeletal muscle but unlike  the muscles of the legs or arms, for instance, unless we have some training we have little awareness of using it. By getting to know the psoas you go deeper with yoga.

the muscles of the legs or arms, for instance, unless we have some training we have little awareness of using it. By getting to know the psoas you go deeper with yoga.

Sitting at a desk or in a car, cycling, power gym crunches, stress and general ‘holding on’ are some elements that contribute to a tight psoas. Sedentary life style and too much being in the mind can mean an underactive psoas. Muscle type, ‘tight’ or ‘loose’, is due to genetics too. Whichever your lifestyle or genes, yoga helps.

In the class we contract the psoas in the leg raises,  a perfect gentle toning. The boat, navasana, (see gentle and more experienced versions, right), makes a strong contraction. Lunges, as in anjanayasana and triangle variations, as well as warming up in sun salutation, lengthen the muscle. Setu bandhasana or bridge is also good. Stretching the arms up while pulling the shoulder blades down will lengthen the upper part of the psoas. It is part of the muscle group called hip flexors that bring the thigh to the body. After sitting forward bend (bringing torso to the thighs) we practise the counter pose, inclined plane, or the less onerous table, to stretch out.

a perfect gentle toning. The boat, navasana, (see gentle and more experienced versions, right), makes a strong contraction. Lunges, as in anjanayasana and triangle variations, as well as warming up in sun salutation, lengthen the muscle. Setu bandhasana or bridge is also good. Stretching the arms up while pulling the shoulder blades down will lengthen the upper part of the psoas. It is part of the muscle group called hip flexors that bring the thigh to the body. After sitting forward bend (bringing torso to the thighs) we practise the counter pose, inclined plane, or the less onerous table, to stretch out.

There’s a way of practising yoga which is about outer alignment and ‘getting it right’, a beginners approach, and rightly so, as a certain level of technique, gross flexibility and strength is needed to progress. As students get more experienced and listen in we are able to develop and hold postures in a process of observation, experiment, testing, reflecting. In my observation, the psoas muscle really works on this intuitive level. As the psoas links to the lowest throrcaic vertebra, also the attachment for the diaphragm, focus with the yogic breath serves to deepen this connection.

The psoas is deep inside, literally and metaphorically. Think of the fluid movement of a dancer or yogi where there is psoas connection: a feeling of relaxation and joy arises. Compare this with the image of a person moving stiffly or with little range, ‘uptight’; maybe you feel a little sad and compassionate for what life might have thrown them. The psoas, in it’s role as hip flexor, brings us into the foetal postion, pulled up into a ball which is the fear position. The psoas holds on to past trauma and working with it allows release.

Yoga is a long letting go. If you’ve been to a yoga class you know you feel more relaxed afterwards. With regular practice you will clear yourself of past ‘stuff’ and then move on to a maintenance programme of regular emotion release, well-being, and develop greater equanimity and courage in the face of all life throws you. It starts with those fascinating leg raises!